The Panther Newspaper: Ashley Tries Visiting Auschwitz

Graphic by Georgina Bridger.

As a mixed-race individual, I’m often asked about my heritage and I always respond with a little joke, “I’m German, Jewish and Japanese so I’m basically World War II in a nutshell.” But visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum in Poland, where my German and Jewish ancestry violently collided, was no laughing matter. It was easily one of the most powerful and devastating experiences I’ve ever had.

I started my guided tour by walking through the main gate that bears the German saying, “Arbeit macht frei,” which dismally and ironically translates to, “Work makes you free.” It’s estimated that more than 1.2 million prisoners passed through this same entrance, but only about 7,000 were eventually liberated from the concentration camp after a mere five years of operation.

There are 28 blocks in Auschwitz I, most of which were used to house prisoners at almost double capacity. Today, these blocks have been transformed into exhibitions that depict life in the camp — from the arrival of prisoners to their almost inevitable deaths — through photos, drawings and, most staggeringly, items that belonged to those very people. I stared in horror at an entire room filled with 14,000 shoes that were confiscated from prisoners upon arrival (pictured on the left) and dragged myself through the rest of the building which contained piles of suitcases, eye glasses, hair brushes, kitchen supplies, children’s clothing and even artificial limbs.

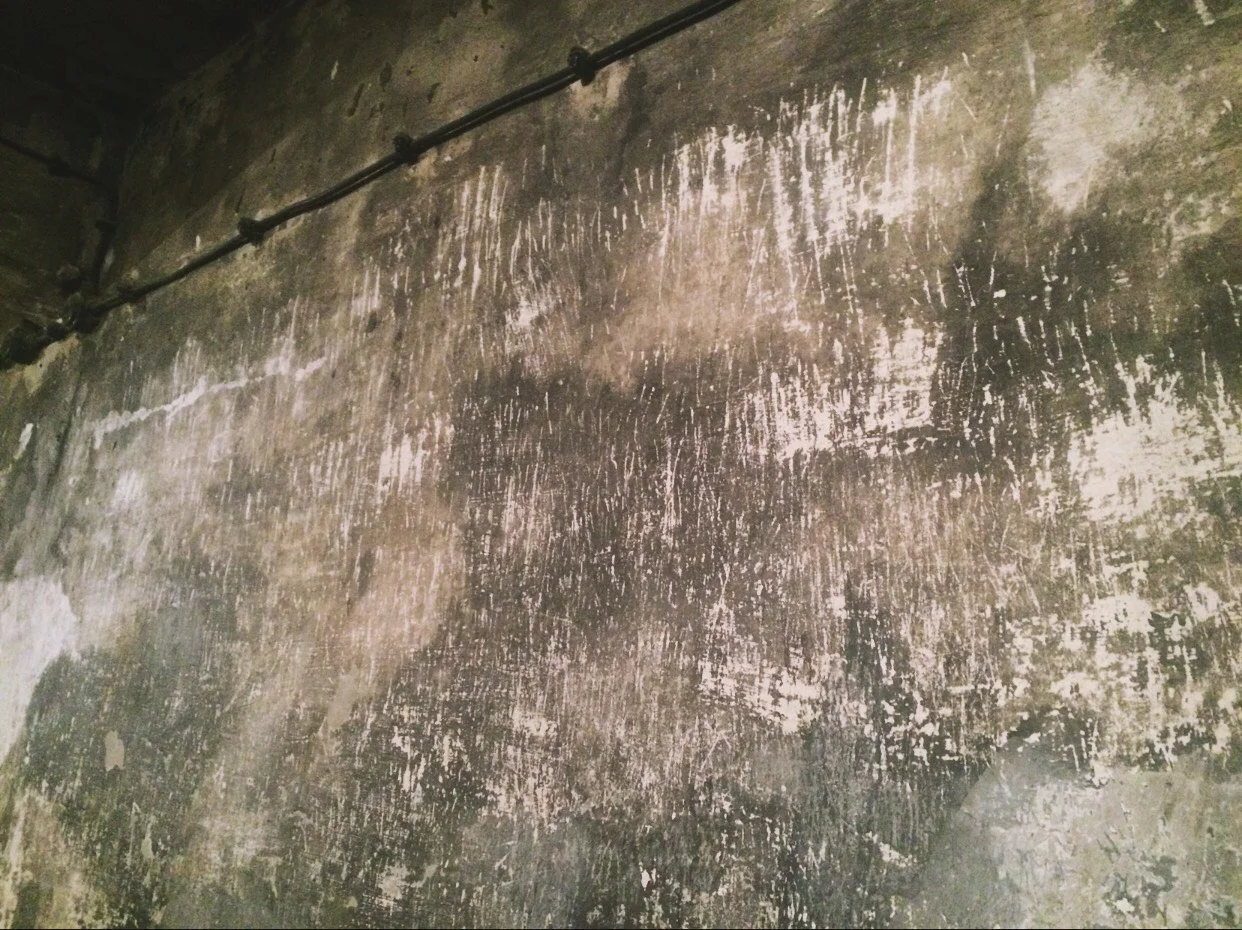

Although I knew that none of my family members were directly affected by the events at the camp, I was paralyzed with shock after walking through a corridor lined with mug shots only to have my gaze lock on one woman who eerily resembled my grandmother, right down to her name. Almost immediately after this discovery, we were led to view the first gas chamber that was used at the camp, where the walls within are covered in scratch marks from victims desperately trying to claw their way out (pictured on the right). This quickly amplified the overwhelming feeling of dread that had been growing exponentially since I stepped foot on the grounds.

Following the tour of Auschwitz I, we took a bus to Auschwitz II-Birkenau where about 90 percent of the camp’s victims died — of which more than nine out of 10 were Jews. I was briefly separated from my tour group and was grateful for the solitary walk along the railway that extends from the entrance all the way to the memorial on the other end of the camp. As I was visualizing the prisoners who walked along the same path after their arrivals, streaks of sunlight pierced through the gray clouds above me as if the souls of the victims were shining down on me to acknowledge my presence. When I reached the end of the line, the sun instantly broke through the thick veil of clouds and my eyes welled up with tears as I imagined those souls extending a warm embrace from the heavens.

At the end of the tour, I took another few minutes to walk among the abandoned buildings and reflect on my experience. As I looked into the windows of each decaying structure, I knew I wouldn’t have been surprised to see a ghostly face staring back at me. I stood among a large patch of flowers, which I found to be a tad incongruous considering a place that was ruled by fear and death is now filled with so much life, but I imagined that there was one flower for each person who met his or her demise in the camp. I closed my eyes and was filled with an intense vibration that I could only interpret as the energy of the millions of souls who had suffered there.

As I was driven away from the camp, I looked back up and could swear that the sun had not moved an inch since I first arrived at Birkenau, but the sky was beginning to fill with a sinister blood-red color even though it didn’t seem like the sun was going to set for a few more hours. I sat in silence for the rest of my journey as I reflected on the haunting, yet spiritual experience that will continue to have an impact on me for the rest of my life.